Outside USMC Camp Schwab, Okinawa, Japan (2019)

My core research area is the study of US base politics, especially focused on civilian-military relations. I am interested in what drives public opinion towards the US military, what drives protests against the US military, and what are the impacts of the US military on the countries and communities that host a US military presence. I am working on several projects that address these aspects of base politics:

Anti-US-Military Activism and Protests:

My dissertation project addresses protest variation between host communities in Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines. Drawing on an original dataset of protest events, primary documents, and interviews, I argue that a key driver of variation is the way in which anti-US-military frames resonate with the local community. I argue that a highly visible US presence in a community that has traditionally been on the political periphery is more likely to help anti-US-military activists’ narrative mobilize opposition to the US military presence.

- Not seeing the forest for the helicopters: UNESCO recognition and resistance to the US military in Okinawa. (Social Movement Studies, 2025).

Previous studies have found that when activists’ demands are not met by their home government, activists may adopt transnational strategies to levy international pressure on their government. While a growing body of literature explores how civil society organizations may take their causes to intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) like the United Nations (UN) to exert pressure on their home governments, it overlooks the variation in the forms of IGOs and the ways that activists use them to exert leverage. The anti-helipad/Osprey movement in Okinawa, Japan, shows how activists may use state-initiated processes of international recognition, such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) World Natural Heritage (WNH) status, to levy international pressure. Drawing on interviews and other primary sources, I demonstrate how environmental activists leveraged the Japanese government’s 2017 nomination of Northern Okinawa (primarily encompassing the Yambaru Forest) to garner international attention for the Northern Training Area (NTA) and its environmental impacts. I argue that this strategy was especially salient in Japan, given the Japanese government’s efforts at crafting a national identity and image as a global environmental leader and a tourist destination. While the WNH designation was ultimately granted, activists’ efforts pressured the Japanese government to release previously private information about the US military presence in the area, as well as opened a channel for future international pressure.

- The Protests about the US Military Abroad (PUMA) Dataset Version 2.0

The US military maintains the largest troop presence in the world, with as many as 800 military installations abroad. While recent research suggests that there are generally positive civilian-military relations in countries that host a US military presence, protests periodically occur and can draw thousands of participants. When and where do these protests happen? What are protesters’ grievances? To date, no publicly available dataset yet exists that can answer these questions. In this project, I propose to improve and expand on my as yet unpublished dataset of anti-US-military protests, Protests about the US Military Abroad (PUMA). This data is especially important for scholars and policymakers in the US and abroad as the US military has become more crucial to countries’ national security in Europe and Asia and countries such as China have started competing with the US for basing access in Africa and other regions.

The working paper using the first version of the dataset can be found here: The Right Frame of Mind? An Analysis of Global Anti-US-Military Protests

- Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Resistance to the US Military in the Philippines

While the Philippines once hosted some of the largest and most strategically important US bases in the Indo-Pacific, it witnessed one of the few successful anti-US-military movements in which activists influenced Filipino policymakers to terminate the US’s basing access in the early 1990s. However, the Philippines has allowed a small contingent of US troops to use some of its own military bases on a temporary basis since the late 1990s through the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA). This renewed US troops presence has faced fewer and smaller protests than before the US’s departure in 1992 despite the similarities in how activists problematize the US military. What accounts for this disparity? I argue that this difference is mostly due to differences in the political opportunity structures around the US troop presence and the way activists’ frames are received. While activists still frame the US presence as a violation of Filipino sovereignty, the lowered visibility of the presence in the latter period undermines the credibility of activists’ frames. I use a paired comparison of two episodes of anti-US-military contention, the period leading up to the US’s loss of basing access in the early 1990s and the years around the negotiation of the VFA, to explore the variation in frame resonance.

- Not All Boats Float on the Rising Tide: Third Wave Democratization and Anti-US-Base Movements in East Asia

In many countries, the 1980s was marked by state-society contention and struggles for democracy. This trend was particularly notable in East Asia, where people’s movements led the way for democracy at the end of the decade in South Korea, the Philippines, and Taiwan. South Korea and the Philippines not only shared this historical moment but also bilateral security arrangements with the United States, allowing the US military to station personnel within their borders. In both countries, the US military presence elicited local resistance due to concerns about crimes committed by military personnel, safety, environmental degradation, and national sovereignty, among others. Despite these similarities, there is a striking difference between the two countries: while the Philippines’ anti-US-base movements were successful in their struggle to remove the US bases from within their borders, South Korean movements were not as successful. I demonstrate through qualitative case analysis that this difference is primarily because Filipino activists linked anti-base contention with the struggle for democracy whereas their South Korean counterparts did not.

Public Opinion and the US Military

- The Enemy of My Enemy is My Friend: Threat Perception, Crime, and Public Support for the US Military (with Myunghee Lee, Michigan State University, and Alexander Jensen, University of Central Florida)

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have examined the domestic and international aspects of US base politics as competition between the US and other great powers intensifies. The literature has explored several different factors that impact a hosting nation’s public opinion towards the US military, including economic benefits and contact with US military personnel. However, much less attention has been paid to the impact of threats and crime attributed to US troops on host nation public opinion. In this study, We fill a gap in the literature by examining the effect of these two additional factors on public support for the US military presence in South Korea and the Philippines. We conduct a survey experiment in both countries and scrutinize the effects of threats posed by China and the occurrence of sexual assault on the host nation’s public opinion. We argue that when the public perceives the levels of threats from China as high, they are less likely to oppose the US military presence. While sexual assaults attributed to the US military are likely to be associated with more opposition to the US military presence, we hypothesize that their impacts on public opinion about the US military are not as strong as the impact of threat perception.

Impacts of the US Military Presence

- Sites of Contention? Environmental Justice and the US Military (with Diva Bello, Skidmore ’25)

Environmental justice has gained traction in recent years as the world increasingly recognizes the disproportional impact that environmental hazards have on historically marginalized populations, including communities of color, indigenous communities, and/or under-resourced communities. One area that has received recent attention is the impact of environmental degradation related to US military bases on local populations. However, there is little research in this area in political science. In this paper, we introduce an original dataset of US military base sites in the US that includes variables to measure historical marginalization and the environmental impacts of the bases. Given the extensive reach of its military presence and its potential impact on historically marginalized communities worldwide, we focus on the US military. This project contributes to discussions of militarization and environmental reparations and raises important questions for policymakers in the US and beyond about basing decisions.

Fieldwork

I have conducted fieldwork in Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines for my book project. Some tips from my fieldwork experiences, especially as it pertains to interviews: Conducting Fieldwork

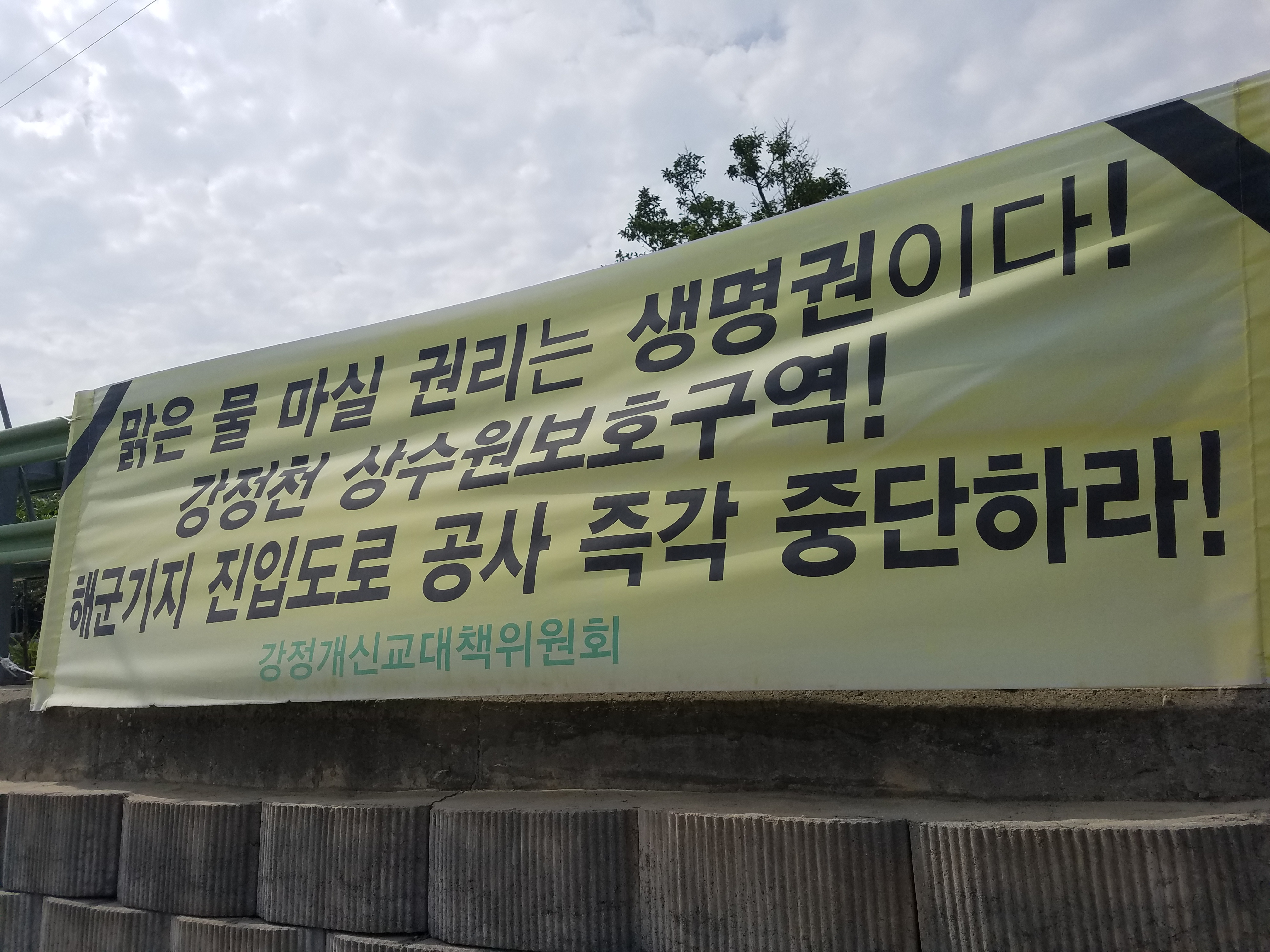

“The right to drink clean water is the right to life! Gangjeong Water Source Protection Area! Stop construction of the access road to the naval base immediately!”

Outside Jeju Civilian-Military Complex, Gangjeong, South Korea (2021)

“’Lord, I hear the sound of the river. The river water raises the sound of the waves.’ (Psalms 93:3) Immediately stop the construction of the military road that destroys the mandarin ducks and the Jeju water of life!”

Outside Jeju Civilian-Military Complex, Gangjeong, South Korea (2021)

Henoko Protest Site, Okinawa, Japan (2019)

Henoko Protest Site, Okinawa, Japan (2019) (Site occupied for 5575 days or about 15 years)

Inside Subic Bay Freeport Zone, Philippines (2019)

Outside Yongsan Garrison, Seoul, South Korea (2018)